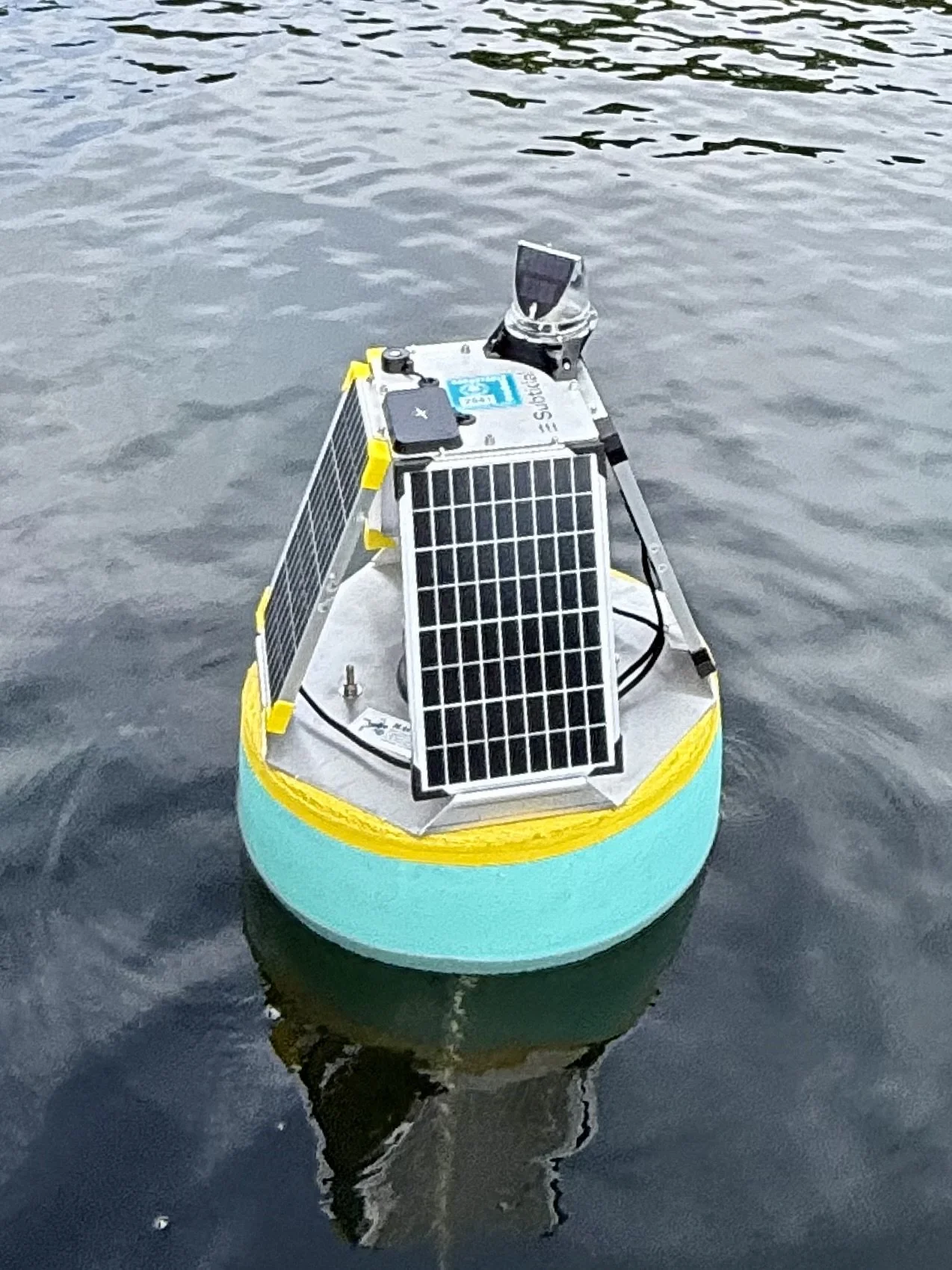

Join us in welcoming “Cupcake” to our pond! The solar-powered buoy was deployed today in the west end of the pond to monitor our waters. Its purpose is to detect, forecast, and help understand the root causes and mitigation of harmful cyanobacteria blooms.

We are excited to be part of this pilot program run by Subtidal, a Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution spin-out, supported by NOAA and the National Science Foundation.

Subtidal Co-Founder and Chief Scientific Officer Matt Long put the buoy in the water today, and activated it to begin collecting and transmitting data. We will soon have access to an online dashboard with real-time water condition data, which will enable us to respond more quickly to changes in our cyanobacteria levels.

We are one of only five areas on Cape Cod to take part in the program so far. The others include Long Pond in Marston Mills and Waquoit Bay.

The research buoy, which was designed for marine systems, is rugged and designed to withstand harsh weather and water conditions. Long says feel free to take a look at “Cupcake” next time you’re out on the pond, but warns not to touch it or try to tie up to it.

In case you’re wondering, “Cupcake” received its name from the six-year-old daughter of the other Subtidal Co-Founder Casey Wilson. You can find out more about Subtidal and the pilot program on its website.